Mary Ellen McDermott: Akron’s Enamel Luminary Who Dared to Change the Course of Metalsmithing

This morning, as the first hush of daylight slipped across my studio table and steam rose from my chipped mug, I found myself searching for an artist to write about—someone who had altered the course of metalsmithing history and, with any luck, had roots tangled close to my own in Ohio soil.

I thought of John Paul Miller and his golden granulations—Cleveland’s proud son—and nearly reached for my phone to text my dear friend, the ever-encyclopedic jewelry historian Jason Adams, for a spark of inspiration. But before my thumb could dance across the screen, a name, long stored in the attic of my mind, unfurled itself like a ribbon.

Mary Ellen McDermott.

An artist not just from Ohio, but from Akron—my own stomping grounds, city of tire kings and tireless makers. A woman who moved through a mid-century world with grace and ferocity, redefining what studio jewelry could be, one luminous enamel panel at a time.

I first crossed paths with Mary Ellen’s legacy in 2017, while co-curating a metalsmithing and enameling exhibition at the Peninsula Art Academy. Carol Adams, my co-curator and an Akron art legend in her own right, caught my arm, looked me squarely in the eyes, and said, with all the weight of history behind her:

“Do you know who this is?”

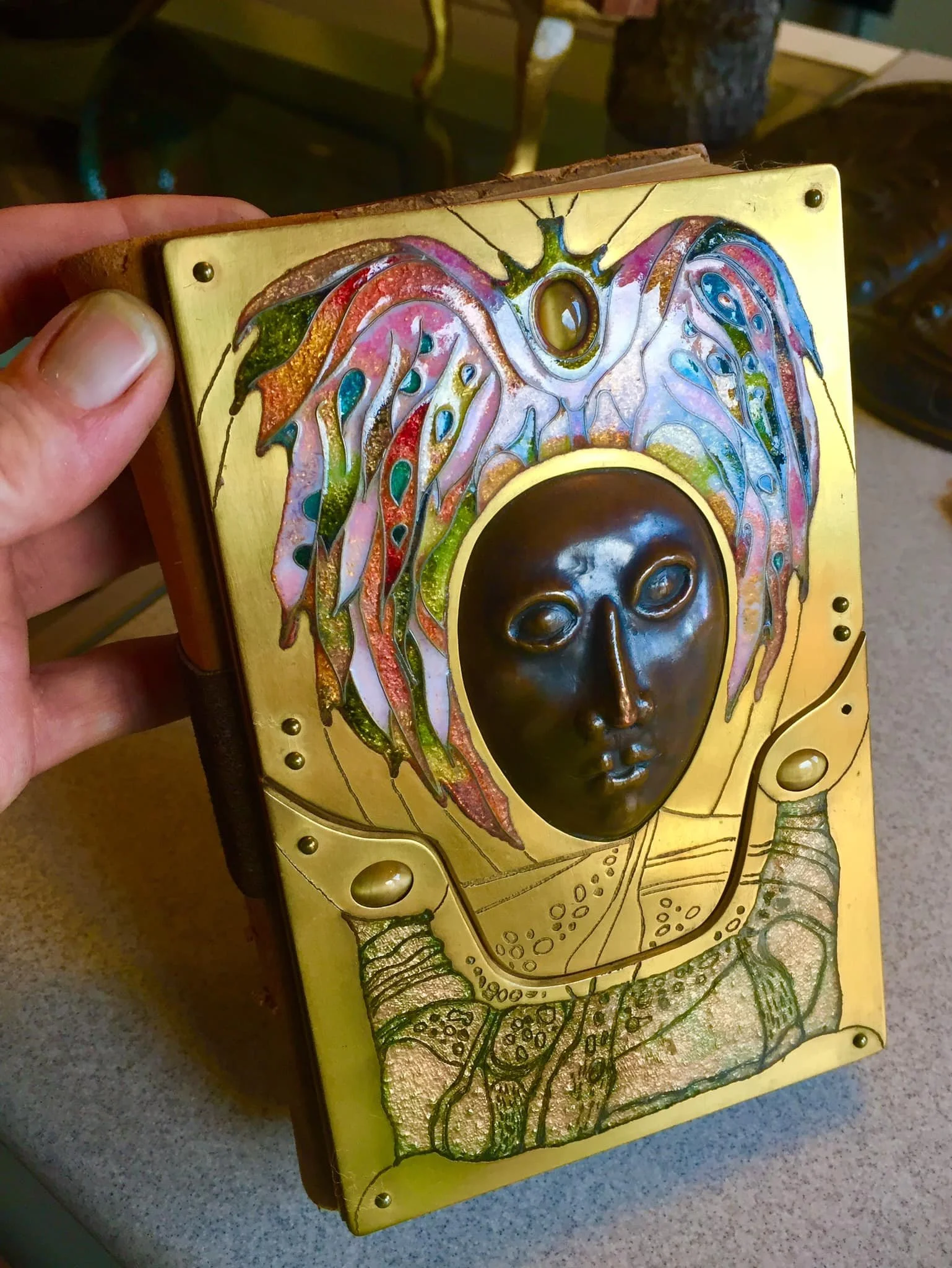

She was pointing to a collection of works by Mary Ellen McDermott—pieces so radiant with color and possibility they seemed to vibrate under the gallery lights. During that show, I was even lucky enough to hold some of Mary Ellen’s historical pieces in my own hands, borrowed from her foundation. (My hand, immortalized, ended up right on the cover of the show’s book.)

Akron is often overshadowed by Cleveland’s industrial arts heritage, but here was proof that our city, too, had birthed a titan. Born Mary Ellen Nichols in 1919, right in Akron’s embrace, she pursued an education at the Cleveland School of Art (now the Cleveland Institute of Art), graduating in 1940 with a BFA focused on painting, watercolor, fashion illustration, and jewelry design. Soon after, she married and took the name McDermott.

Her journey with enamel—a notoriously demanding medium—was not immediate. It wasn’t until around 1953, well into her thirties and after years teaching painting and drawing at the Akron Art Institute, that she truly began to explore its depths. Enamel is glass, ground into a powder so fine it whispers when poured, sifted onto copper sheets, then fired at 1700 degrees Fahrenheit until it melts into liquid light. These were not paintings. These were architectural works of art: vivid, large-scale sculptures made of earth’s oldest materials, fused by fire.

By 1961, at the age of 42, she returned to Cleveland to teach, ultimately rising to chair the Enamel on Metal Department by 1968. For nearly two decades she shaped a generation of artists there, known as a free spirit and a profoundly tolerant teacher who urged her students to chase the limits of what enamel could do. She was, in every sense, a force—a woman who carved a space for herself in a field dominated by men, and then threw open the door for countless others.

In a 1955 Cleveland Plain Dealer interview titled “Puts Her Art on Enamel Panels,” she captured her medium’s eternal allure:

“Enamel is one of the ageless art mediums. It is more permanent than oils and it never fades. You can get effects in enamel you can’t get in any other way because it is translucent and it looks precious to begin with.”

Imagine the audacity it took for a woman in mid-century Ohio—amid all the stiff collars and expectations—to stand before a roaring kiln and conjure such fragile, molten magic. To insist on a life of art. To become the teacher’s teacher.

Mary Ellen McDermott didn’t just change metalsmithing; she embodied its molten heart. She is a thread in Akron’s artistic tapestry that continues to glint brightly, reminding us what’s possible when talent meets fearless exploration.

Marie Zimmerman

Imagine being so undeniably good they simply couldn’t ignore you.

Marie Zimmermann (1879–1972) was that kind of extraordinary. Born in Brooklyn to Swiss parents, she mastered a dozen crafts—metalsmithing above all. Her hands conjured repoussé boxes alive with mythic beasts, silver bowls that rippled like water, gem-laced brooches that could’ve graced a pharaoh.

She wove ancient Greek, Egyptian, and Renaissance motifs into something utterly her own—a lush, American aesthetic that referenced centuries. Critics called her “perhaps the most versatile artist in the country.” Her works were scooped up by industrial titans, shown in major exhibitions, and today rest in the Met, the Art Institute of Chicago, and more.

Make no mistake: she had to be better.

In the early 1900s, for a woman to flourish in metalsmithing—let alone at this scale—she couldn’t simply match her male peers. She had to dazzle, astonish, transcend.

And transcend she did.

At a time when most women were confined to “delicate” arts, Marie rolled up her sleeves and did something nearly unheard of:

She directed a team of men—blacksmiths, silversmiths, casters—at the National Arts Club in New York.

Seasoned craftsmen took her lead, translating her fearless visions into wrought gates, chased silver, architectural fixtures, and intricate jewels. She didn’t just wield a hammer—she wielded authority, orchestrating workshops that blurred the line between object and poetry.

Zimmermann made her living through commissions—bronze doors for estates, ecclesiastical silver, jewelry for New York’s elite. Yet she lived largely on her own terms, never marrying, finding solace at her beloved farm in Pike County, PA.

Though celebrated in her day, her story still feels like a hidden treasure waiting to be unearthed by those who truly understand what it took to stand at the helm of a metals studio back then.

Marie Zimmermann was fire and alloy—beauty conjured from grit. She was not just a maker of objects, but a maker of possibilities, forging paths for all who’d come after.

If you didn’t know her name before, now you do.