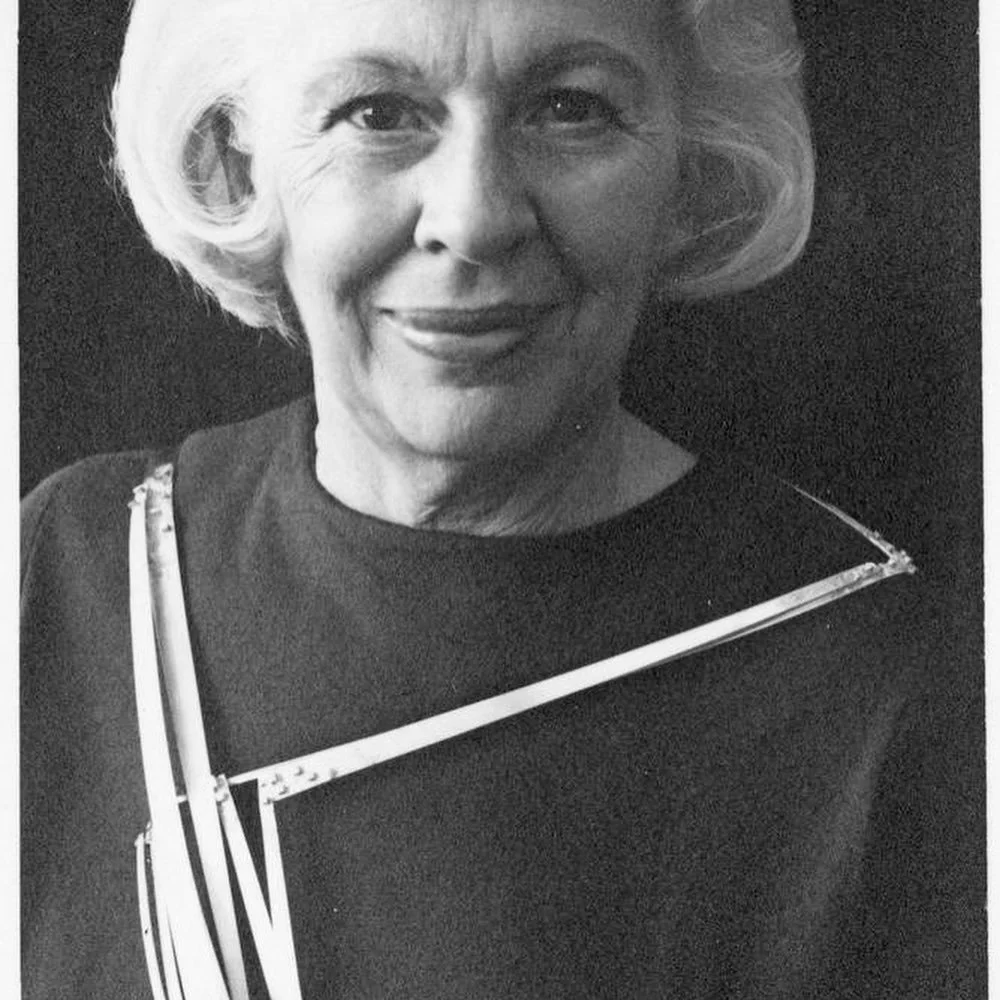

🔨 Kindred Forms: A Tribute to Sharon Church

I only recently discovered the work of Sharon Church (1948–2022)—and yet, it felt like something in her work already knew me.

Church was a studio jeweler and educator whose materials spoke in hushed tones: boxwood, antler, bone, silver. She carved delicate botanical forms—vines, wings, claws, flowers—that were neither ornamental nor ornamentalist. They were symbols, carved stories, emotionally resonant objects. Her jewelry didn’t shout. It whispered, remembered, and endured.

She came of age during a time when women were still fighting for recognition in metalsmithing and academia. Trained at Skidmore College and the School for American Crafts at Rochester Institute of Technology, Church entered the field quietly, with focus and determination. In the 1970s she began a long and influential teaching career at the University of the Arts in Philadelphia, where she mentored generations of metalsmiths, especially women and LGBTQ+ artists. Her studio practice and teaching philosophy were deeply intertwined—she believed in craft as care, and that making was a form of both communication and survival.

In 1993, Sharon’s husband died suddenly. This loss marked a transformation in her work. Forms that had once been elegant and mysterious became more emotionally raw—still graceful, but haunted. Wilted flowers. Sprouting pods. Jewelry that mourned and bloomed in the same breath.

She once said:

“I don’t draw a line between technique and meaning—they are the same thing.”

That quote struck me with full force.

I’ve written extensively about how Craft serves as a healing modality—how materials, movement, and embodied practice can support grief, stress recovery, and emotional repair. In my own experience, metalsmithing has often been a way to shape emotion into form—to alchemize pain, presence, and memory through molten metal and hand tools. I work with fire, carving tools, and gravity. So did Sharon. Though I never met her, and only encountered her work posthumously, I felt something like kinship.

There’s a term I use often in my teaching and research: materiality, identity, and transformation. Sharon Church’s legacy sits at the intersection of all three. Her materials were raw and humble. Her forms held personal and symbolic weight. And her process transformed loss into something wearable—something remembered.

We often think of legacy in terms of prestige or fame. But Sharon Church’s power was in her presence—in the quiet steadiness of her work, the precision of her hand, and the generosity of her teaching. Her jewelry doesn’t merely exist. It listens. It holds space. And it invites us to do the same.

Thank you, Sharon, for carving a path where quiet stories live.

You are remembered.

✦ The Hansen Legacy: Karl Gustav Hansen and the Enduring Spirit of Danish Silver ✦

Our journey through Scandinavian silversmithing has already introduced you to the visionary artistry of Björn Weckström, Heikki Seppä, Hans Hansen, and Georg Jensen. This week, we turn our focus to Karl Gustav Hansen—a designer whose legacy extends far beyond the shadow of his father, Hans Hansen, and into the enduring heart of Danish modernism.

A Silversmith Born of Silver

Karl Gustav Hansen was born on December 10, 1914, in the coastal town of Kolding, Denmark. His father, Hans Hansen, had established a silversmithing workshop there 15 years prior, laying the foundation for a family dynasty that would shape 20th-century Scandinavian design. The young Karl grew up surrounded by the quiet clink of hammers and the shine of polished metal. By his teenage years, he left formal Craft school early and began apprenticing with silversmith Einar Olsen—whom he had met in his father’s workshop. His path was set.

Upon completing his apprenticeship, Karl returned to the family shop, where his early talent blossomed. At just 20 years old, he designed a teapot and chafing dish so elegantly resolved that they earned him a scholarship to study sculpture at the prestigious Royal Danish Academy of Fine Arts. There, under the sculptor Utzon Frank, Karl honed his understanding of form, volume, and balance—skills that would later define his aesthetic.

Form, Function, and Forward Thinking

When Hans Hansen passed away unexpectedly, Karl—only 25—stepped in to helm the family business. Far from being a caretaker of tradition alone, he evolved the studio’s vision with an eye toward the modern. Karl Gustav Hansen’s work is characterized by a deep reverence for material, balanced by innovation in form. Even in times of hardship, his values never wavered.

During World War II, silver became scarce, and many historic silverworks across Denmark were melted down for reuse. Rather than allow these heirlooms to vanish, Karl took a bold risk: he purchased and preserved them. His reverence for Craft history and thoughtful stewardship of material culture stands as a profound act of resistance against the tide of destruction.

In his own designs, Karl responded to scarcity with ingenuity. He created elegant, efficient pieces that conserved material while maximizing impact. His iconic Heart and Box series exemplify this approach—minimal yet expressive, spare yet unforgettable.

A Family Story Etched in Silver

For over four decades, Karl maintained the Hans Hansen workshop with devotion and distinction. But personal tragedy struck again in the early 1980s when his own son, also named Hans, passed away unexpectedly. Grieving both his father and son, and facing financial instability, Karl made the difficult decision to merge the family business with the Georg Jensen Company—a move that marked both an end and a continuation.

Karl Gustav Hansen passed away in 2002, but his legacy endures in every thoughtfully wrought curve, every design that whispers of function made beautiful. His life reminds us that silversmithing, like all art, is not just about what we make—but how we carry forward the values of those who came before.

Alma Eikerman: The Quiet Force Who Shaped Metalsmithing Education

For anyone who has studied the history of Craft with care, Alma Eikerman is more than a name—she’s a blueprint. A revolutionary force tucked into the folds of academia, she quietly, steadfastly reshaped what it meant to learn, teach, and master metalsmithing in America.

Eikerman didn’t just make jewelry—she made standards. The structure of today’s graduate programs in metals and jewelry? Much of it follows the contours of her vision. Her influence is so deeply embedded in our institutions that it can be difficult to trace back to the woman herself. Her physical works are rarely seen; her legacy lives instead in syllabi, critiques, studio habits, and the very idea that metalsmithing belongs in the university.

Born on May 16, 1908, in Pratt, Kansas, Alma was raised on a working farm by a family who honored creativity with their hands. Her earliest studies weren’t in art, but in history, literature, and language—a foundation that would later lend poetry and structure to her teaching. She began her professional life as a schoolteacher, only later returning to Kansas State to pursue the arts. After transferring to Columbia University, she earned her Master’s in 1942 with a specialization in metalsmithing, painting, and design—a rare and radical combination at the time.

When World War II erupted, Alma joined the Red Cross and traveled to Italy, where she served her country and continued her study of design. Returning stateside in 1947, she joined the faculty at Indiana University, where she didn’t just teach—she transformed. Her energy reinvigorated the metals program, and on a sabbatical in 1950, she expanded her knowledge even further by studying with Danish master Karl Gustav Hansen, as well as Henrick Boesen and Erik Fleming.

Upon returning to Indiana University, Alma began integrating hollowware into her studio practice, pushing the boundaries of what jewelry and metal art could encompass. She didn’t stay in one lane; she widened the whole road. Her work was experimental, elegant, and steeped in function—a quiet rebellion against ornament for ornament’s sake.

By 1970, she had co-founded SNAG, the Society of North American Goldsmiths, cementing her place in Craft history. Her name became a household word in the American metals community, and her presence an aspirational figure for countless women entering the field. She was more than a metalsmith—she was a model of persistence, intellect, and excellence in a male-dominated world. A Distinguished Professor Emeritus at Indiana University, she retired at the age of 70, leaving behind not just objects, but a movement.

Alma Eikerman passed away on January 3, 1995, in her Bloomington home, surrounded by the quiet echoes of a life that redefined what women could do with fire, metal, and vision.

In her, we see the strength of feminism not in loud declarations, but in methodical, brilliant, lasting change. We honor her not just for what she made, but for what she made possible.

Claire Falkenstein: A Modernist Who Refused to Be Tamed

Claire Falkenstein was a woman who defied gravity—not only in the physical sense, but in the social, artistic, and historical senses as well. Born on July 22, 1908, in Coos Bay, Oregon, she grew up wild with wonder, riding horses along the beach in the dark and falling in love with science. That restless curiosity never left her. It lived in her hands, in her metal, in her fierce commitment to pushing form beyond its boundaries.

Falkenstein was a sculptor, a metalsmith, a painter, a printmaker, a jeweler, and a teacher. But more than any title, she was a force—untamed and unscripted. She forged new paths not just through material, but through ideology. She challenged the false hierarchy between fine art and craft, and refused to confine herself to one category. She didn’t need to “fit in”—she invented new spaces instead.

She began making jewelry in the 1940s as a way to bring her sculptures to the human body. It was never about decoration—it was about translation. Her works were extensions of her larger sculptures, explorations in space, line, and kinetic energy. She became a contemporary of Alexander Calder, but unlike Calder, Falkenstein's work rarely earned the spotlight it deserved. She didn’t court commercial success, and she didn’t settle in one place long enough to be pinned down by critics or curators. She was too busy making.

In post-WWII America, where women were expected to shrink or serve, Falkenstein expanded. Her art was radical not only for its formal innovation but for its refusal to ask permission. She worked in iron and glass, twisted copper, and shattered assumptions. Her wearable pieces were not subordinate to her sculptures—they were sculptures, intimate ones. Sculptures that moved with the body, that lived on skin.

And yet, she is often overlooked—her legacy scattered like her travels, her work under-documented, her name absent from too many textbooks. But absence does not equal insignificance. Falkenstein’s absence is a reflection of the systems that failed to see her, not the value of what she made.

Her life and work remind us that the boundaries between disciplines, like the boundaries placed on women, are meant to be broken. That art can be wild and free. That we do not need to choose between intellect and intuition, structure and spirit, body and object. We can have all of it.

She is a model for those who make without waiting for approval. For those who don’t ask if it’s art or craft or jewelry or sculpture. For those who simply begin, and keep going.

Ohio’s Quiet Fire: The Legacy of Kenneth F. Bates and the American Enameling Renaissance

Ohio has always carried a quiet, persistent flame for the arts—flickering through workshops, studios, and classrooms, waiting to ignite new hands and hearts. In the early 20th century, Cleveland became an unlikely crucible for American enameling, that exquisite fusion of glass and metal that seems almost alchemical in its glow.

At the center of this transformation stood Kenneth F. Bates, a visionary artist and educator who taught at the Cleveland Institute of Art for nearly fifty years. Bates quite literally wrote the book on enameling, shaping not only the curriculum but the very language of modern American enamel art. His careful guidance, passion, and ceaseless experimentation turned copper and silver into canvases of luminous color—vivid stories coaxed from fire.

Bates’ influence didn’t stop with his own remarkable work. His students—and their students—carried these techniques and philosophies across the country. They breathed new life into ancient practices, pushing boundaries, forging modernist jewelry, and proving again that craft is a lineage of both skill and heart. From delicate cloisonné to bold abstract panels, the legacy of Ohio’s enameling pioneers lives on in countless studios today.

Now, more than a century later, we find ourselves in the midst of a quiet renaissance. Enameling is blooming all over again. Artists across Ohio and the broader American craft community are drawing luminous narratives from their kilns. You can spot these vibrant creations at art fairs, intimate gallery shows, and shared proudly across social media—sparking wonder in the most ordinary of moments.

As makers and appreciators, we inherit more than just technique. We inherit a way of seeing: of honoring process, of caring deeply for materials, of leaving thoughtful traces behind for others to build on. What we create, teach, and pass along becomes part of a ripple that can extend long after we are gone.

So here’s to Kenneth F. Bates, to Ohio’s enduring fire, and to all of us still tending it—one brushstroke of enamel, one hand-raised torch at a time. May we continue to experiment, to teach, to create, so that the next generation has something luminous and lasting to stand upon.

John Paul Miller: Ohio’s Master of Gold Dust and Dream Creatures

This morning, I found myself thinking about the quiet revolutions that happen in small studios — the alchemy of patience, fire, and human hands. It brought me back to John Paul Miller, a name that hums through the history of American metalsmithing like a well-kept secret.

Miller is often hailed as the father of American granulation. If you’re not familiar, granulation is a near-mystical process of fusing hundreds — sometimes thousands — of minute gold or silver spheres onto the surface of a piece, building delicate constellations of metal that catch the light like a galaxy trapped in amber.

It’s an ancient art. The oldest known example was found in the royal tomb of Queen Pu-Abi in Ur, Sumer — five thousand years ago. Imagine: Miller’s goldsmith’s bench in Cleveland somehow linked by an unbroken filament of craft to the palace workshops of Mesopotamia.

Though born in 1918 in Huntington, Pennsylvania, Miller’s heart and legacy are purely Ohio. As a child, his family settled in Cleveland, where he began taking Saturday art classes at the Cleveland School of Art (now the Cleveland Institute of Art). After high school, he returned there to formally study Design and Industrial Arts. Even then, he was sketching out a life that wove together beauty and utility.

World War II briefly pulled him away. Enlisted in the Army, his artistic gifts found their place designing maps and instructional manuals for the Training Literature Department of the Armed Forces. But after the war’s echo faded, Cleveland called him back, and the School welcomed him home — this time to teach. It was there, among the earnest chatter of students and the quiet hum of studio tools, that Miller truly sank into metalsmithing. Silver, gold, enamel — he chased their secrets with a devotion that bordered on spiritual.

Granulation, however, would become his lasting signature. Unlike many modern jewelers, Miller turned backward through time, studying Etruscan and Sumerian pieces, experimenting relentlessly to master their elusive techniques. By the time he succeeded, he wasn’t simply reviving an old art form; he was reinventing it, leaving behind brooches and rings that feel like something plucked from a myth — alive with tiny fantastical creatures and the shimmer of gold dust.

“There’s no question I wanted it to be beautiful,” Miller once said.

“I didn’t want it to be kinky or unique particularly or something that was avant-garde or anything. I just wanted it to be beautiful.”

And beautiful it was. His jewelry is a menagerie of small wonders — seahorses, lizards, delicate insects — rendered in granulated gold and vibrant enamel. Pieces that, even decades later, still seem to breathe.

Miller remained in Cleveland all his life, passing in 2013, surrounded by people who loved him not only for his brilliance at the bench but for his gentle nature. Those who knew him speak of a lifelong artist, a humble teacher, and a man deeply in tune with the natural world he so often immortalized in metal.

In a field sometimes driven by ego and novelty, Miller stood apart, chasing neither shock nor spectacle. He pursued beauty — pure and simple — and in doing so, he left an indelible mark not just on American studio jewelry, but on the very language of ornament.

So here’s to John Paul Miller:

Cleveland craftsman, alchemist of ancient gold, tender conjurer of dream beasts — proof that sometimes, the most profound revolutions begin quietly, in the heart of Ohio.

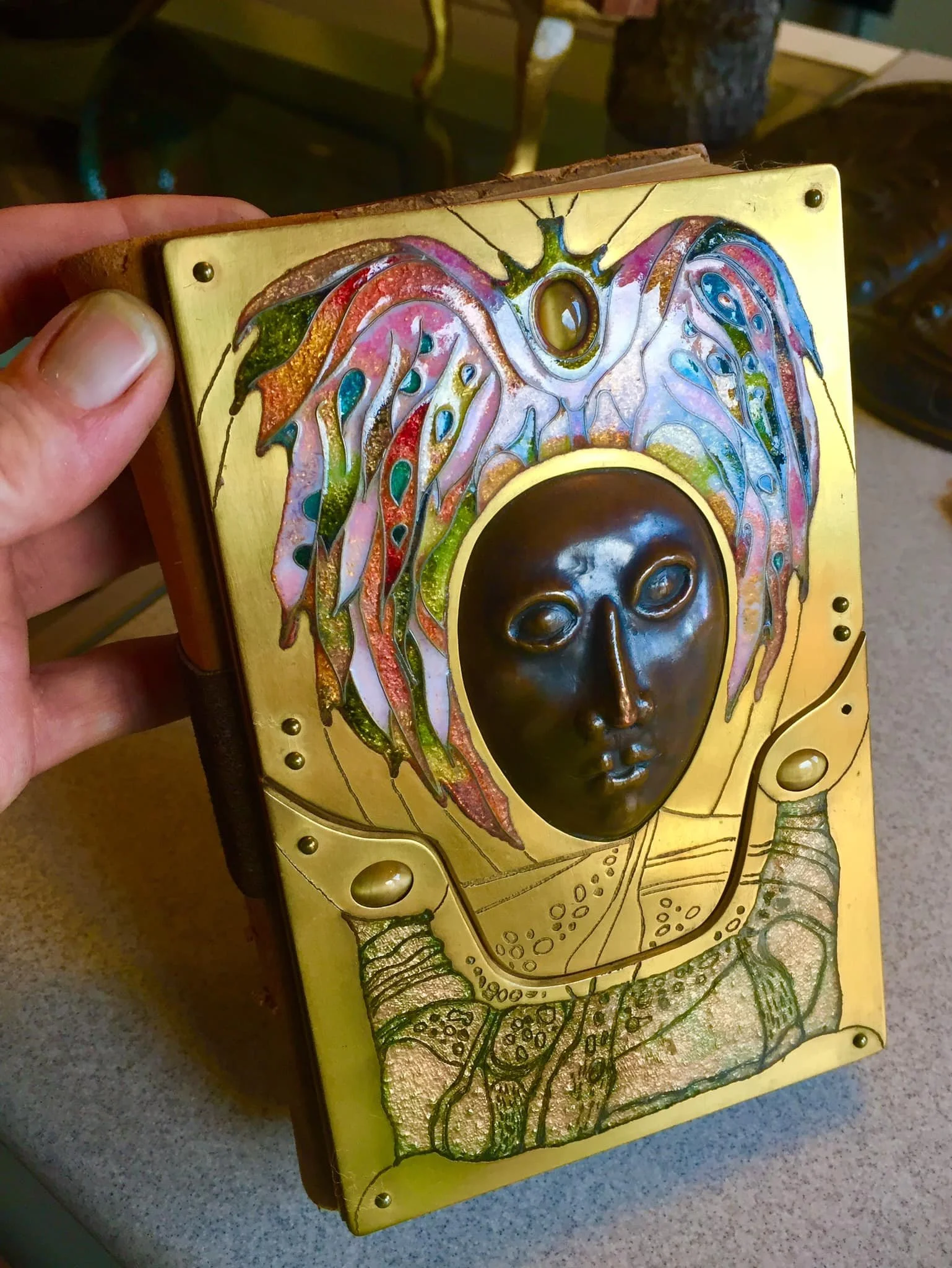

Mary Ellen McDermott: Akron’s Enamel Luminary Who Dared to Change the Course of Metalsmithing

This morning, as the first hush of daylight slipped across my studio table and steam rose from my chipped mug, I found myself searching for an artist to write about—someone who had altered the course of metalsmithing history and, with any luck, had roots tangled close to my own in Ohio soil.

I thought of John Paul Miller and his golden granulations—Cleveland’s proud son—and nearly reached for my phone to text my dear friend, the ever-encyclopedic jewelry historian Jason Adams, for a spark of inspiration. But before my thumb could dance across the screen, a name, long stored in the attic of my mind, unfurled itself like a ribbon.

Mary Ellen McDermott.

An artist not just from Ohio, but from Akron—my own stomping grounds, city of tire kings and tireless makers. A woman who moved through a mid-century world with grace and ferocity, redefining what studio jewelry could be, one luminous enamel panel at a time.

I first crossed paths with Mary Ellen’s legacy in 2017, while co-curating a metalsmithing and enameling exhibition at the Peninsula Art Academy. Carol Adams, my co-curator and an Akron art legend in her own right, caught my arm, looked me squarely in the eyes, and said, with all the weight of history behind her:

“Do you know who this is?”

She was pointing to a collection of works by Mary Ellen McDermott—pieces so radiant with color and possibility they seemed to vibrate under the gallery lights. During that show, I was even lucky enough to hold some of Mary Ellen’s historical pieces in my own hands, borrowed from her foundation. (My hand, immortalized, ended up right on the cover of the show’s book.)

Akron is often overshadowed by Cleveland’s industrial arts heritage, but here was proof that our city, too, had birthed a titan. Born Mary Ellen Nichols in 1919, right in Akron’s embrace, she pursued an education at the Cleveland School of Art (now the Cleveland Institute of Art), graduating in 1940 with a BFA focused on painting, watercolor, fashion illustration, and jewelry design. Soon after, she married and took the name McDermott.

Her journey with enamel—a notoriously demanding medium—was not immediate. It wasn’t until around 1953, well into her thirties and after years teaching painting and drawing at the Akron Art Institute, that she truly began to explore its depths. Enamel is glass, ground into a powder so fine it whispers when poured, sifted onto copper sheets, then fired at 1700 degrees Fahrenheit until it melts into liquid light. These were not paintings. These were architectural works of art: vivid, large-scale sculptures made of earth’s oldest materials, fused by fire.

By 1961, at the age of 42, she returned to Cleveland to teach, ultimately rising to chair the Enamel on Metal Department by 1968. For nearly two decades she shaped a generation of artists there, known as a free spirit and a profoundly tolerant teacher who urged her students to chase the limits of what enamel could do. She was, in every sense, a force—a woman who carved a space for herself in a field dominated by men, and then threw open the door for countless others.

In a 1955 Cleveland Plain Dealer interview titled “Puts Her Art on Enamel Panels,” she captured her medium’s eternal allure:

“Enamel is one of the ageless art mediums. It is more permanent than oils and it never fades. You can get effects in enamel you can’t get in any other way because it is translucent and it looks precious to begin with.”

Imagine the audacity it took for a woman in mid-century Ohio—amid all the stiff collars and expectations—to stand before a roaring kiln and conjure such fragile, molten magic. To insist on a life of art. To become the teacher’s teacher.

Mary Ellen McDermott didn’t just change metalsmithing; she embodied its molten heart. She is a thread in Akron’s artistic tapestry that continues to glint brightly, reminding us what’s possible when talent meets fearless exploration.

Horace Potter

I’ve been investigating metalsmiths from Ohio who have truly changed the course of history. So far, I’ve highlighted the remarkable work of John Paul Miller and Mary Ellen McDermott—both of whom I discovered on my own. But when I reached out to my friend and jewelry historian Jason Adams, he gave me a few new names to explore, opening up even more layers of our regional craft history.

One that I’m thrilled to include is Horace Potter, a pivotal figure often recognized as the founder and leader of Cleveland’s vibrant Arts and Crafts metals community. His contributions were foundational in shaping not just a local style, but also a culture of teaching and studio practice that would ripple across generations.

Potter was born in 1873 into a well-to-do Cleveland family. At twenty, he enrolled in the Cleveland School of Art (today’s Cleveland Institute of Art), where he immersed himself in traditional design and craftsmanship. After graduating four years later, he sharpened his skills in Boston, earning a master’s degree with a focus on metalsmithing—a fairly specialized pursuit for the time.

At just 27, he returned to teach at his alma mater. But his passion for deep, authentic craft education drew him even farther afield: after a year, he left for England to study at the School of the Guild of Handicraft in Chipping Campden, led by none other than Charles Robert Ashbee, one of the primary visionaries of the British Arts and Crafts movement. This experience profoundly shaped Potter’s philosophy. He absorbed not only technical methods but also the movement’s core belief that beautiful, well-made objects could uplift daily life.

When Potter came back to Cleveland, he brought this ethos with him. He resumed teaching at the Cleveland School of Art, instilling these values in a new generation of American metalsmiths. By 1905, he had moved back to his family’s farm, where he famously transformed a humble chicken coop into a metals studio. Ever the community builder, he invited students and young craftspeople to work there alongside him, fostering a true workshop atmosphere.

Soon after, Potter established a downtown Cleveland studio that moved through several locations along bustling Euclid Avenue, becoming a nucleus for high-quality handcrafted silver and metalwork. By 1928, seeking to expand, he partnered with Gurdon W. Bentley to create Potter Bentley Studios, introducing china and garden accessories to their offerings. Though Bentley dissolved the partnership in 1933, it was only months later that another chapter began: Louis Mellen approached Potter, and together they founded Potter and Mellen, Incorporated—a name still synonymous with fine metalwork and jewelry in Cleveland to this day.

Potter didn’t just make exquisite objects; he helped build an artistic infrastructure. Through teaching, mentoring, and leading by example, he established Cleveland as a significant center for Arts and Crafts metalwork in the United States, drawing on European ideals but shaping them into something distinctly local.

I’ve been dedicating my #tbt posts to studio jewelers and metalsmiths who left an indelible mark on our field. Please feel free to leave your thoughts, memories, or to share—especially if you have stories connected to Cleveland’s rich craft history.

Mary Ann Scherr

I thought she was still alive because I saw her solo exhibition at the Akron Art Museum when I was working there in the late 90’s. I could swear I saw her in person, but that might just be my mind playing tricks on me. I was deeply saddened to learn she passed on March 1st, 2016 at her home in Raleigh, NC at the remarkable age of 94.

Mary Ann Scherr was born on August 3rd, 1921 in Akron, Ohio. A relentless learner, she trained anywhere she could reach by car from Akron, attending the Cleveland Institute of Art (CIA), The University of Akron, and Kent State University. After graduating, she stayed in the Akron area and worked as a cartographer and illustrator for Goodyear. She later made history at Ford Motor Company as the first woman hired in their automotive design division—very cool already, right?

Her creative life was astonishingly multifaceted. She designed toys and games, illustrated children’s books, worked as a clothing and graphic designer, and eventually found her most profound artistic voice as a metalsmith. She taught as an associate professor of metals at Kent State from 1967 to 1978 before accepting a role as chair of the Product Design Department at Parsons School of Design in New York City.

Mary Ann Scherr is especially revered for her pioneering work in medical jewelry. Long before the now-ubiquitous medical alert bracelets, she developed wearable pieces that combined life-saving function with beauty and dignity. Her designs included bracelets that concealed heart monitors, pendants that served as respiratory aids, and elegant adornments embedded with critical medical information—helping transform perceptions of what “assistive devices” could look like. She often worked in stainless steel, niobium, and titanium, exploring innovative processes that were as forward-looking as the healthcare technologies she incorporated. In doing so, she blurred the lines between art, craft, industrial design, and medical engineering.

She is remembered for her energetic personality, her fearless use of exotic metals and new techniques, and for mentoring countless students around the world. By my count, she won over 10 major design and lifetime achievement awards and even had a solo exhibition at the Vatican Museum of Art in Rome.

I’ve been dedicating my #tbt to the history of studio jewelry, recently focusing on Ohio jewelers who forever changed the course of metalsmithing. Please feel free to share or leave feedback—I’d love to hear your thoughts or personal memories.

Marie Zimmerman

Imagine being so undeniably good they simply couldn’t ignore you.

Marie Zimmermann (1879–1972) was that kind of extraordinary. Born in Brooklyn to Swiss parents, she mastered a dozen crafts—metalsmithing above all. Her hands conjured repoussé boxes alive with mythic beasts, silver bowls that rippled like water, gem-laced brooches that could’ve graced a pharaoh.

She wove ancient Greek, Egyptian, and Renaissance motifs into something utterly her own—a lush, American aesthetic that referenced centuries. Critics called her “perhaps the most versatile artist in the country.” Her works were scooped up by industrial titans, shown in major exhibitions, and today rest in the Met, the Art Institute of Chicago, and more.

Make no mistake: she had to be better.

In the early 1900s, for a woman to flourish in metalsmithing—let alone at this scale—she couldn’t simply match her male peers. She had to dazzle, astonish, transcend.

And transcend she did.

At a time when most women were confined to “delicate” arts, Marie rolled up her sleeves and did something nearly unheard of:

She directed a team of men—blacksmiths, silversmiths, casters—at the National Arts Club in New York.

Seasoned craftsmen took her lead, translating her fearless visions into wrought gates, chased silver, architectural fixtures, and intricate jewels. She didn’t just wield a hammer—she wielded authority, orchestrating workshops that blurred the line between object and poetry.

Zimmermann made her living through commissions—bronze doors for estates, ecclesiastical silver, jewelry for New York’s elite. Yet she lived largely on her own terms, never marrying, finding solace at her beloved farm in Pike County, PA.

Though celebrated in her day, her story still feels like a hidden treasure waiting to be unearthed by those who truly understand what it took to stand at the helm of a metals studio back then.

Marie Zimmermann was fire and alloy—beauty conjured from grit. She was not just a maker of objects, but a maker of possibilities, forging paths for all who’d come after.

If you didn’t know her name before, now you do.

Mary Lee Hu

There’s something about Marys (in Ohio).

Maybe it’s just coincidence, but I like to think it’s something in the rustbelt air — all that history of forging, bending, rebuilding — that keeps calling out to Marys to pick up metal and make it tender.

There’s Mary Ann Scherr, born in Akron, who turned jewelry into tools of care, designing beautiful trach necklaces and heart monitors that helped people feel seen, not just treated.

There’s Mary Ellen McDermott, who lived and taught in Akron, Peninsula, and Cleveland, painting copper with molten glass. Her enamel work shimmers like tiny stained glass windows you can hold in your hand.

And then there’s Mary Lee Hu, from Lakewood, who wove gold so fine it nearly breathed. She was born by Lake Erie in 1943 and somehow carried the lake’s rippling patience with her. Over decades, she twisted tiny loops of wire into fabric-like sculptures that drape across the body. It’s a choreography of hands, breath, and steady attention that feels so close to how many of us soothe ourselves — through slow, tactile making.

There’s no neat story of depression or illness to pin to Mary Lee Hu the way we might with an Agnes Martin or a Frida Kahlo. But you can feel the same meditative pull in her process: the tiny, deliberate gestures that take chaos and turn it into something intricate, gentle, and strong.

I love the grace of that. The idea that through repetition — whether carving cuttlebone or looping gold wire — we can quiet our own storms, if only for a little while.

If you’ve got a favorite artist whose hands worked like this — slowly, patiently, turning mess into meaning — I’d love to hear.