Ohio’s Quiet Fire: The Legacy of Kenneth F. Bates and the American Enameling Renaissance

Ohio has always carried a quiet, persistent flame for the arts—flickering through workshops, studios, and classrooms, waiting to ignite new hands and hearts. In the early 20th century, Cleveland became an unlikely crucible for American enameling, that exquisite fusion of glass and metal that seems almost alchemical in its glow.

At the center of this transformation stood Kenneth F. Bates, a visionary artist and educator who taught at the Cleveland Institute of Art for nearly fifty years. Bates quite literally wrote the book on enameling, shaping not only the curriculum but the very language of modern American enamel art. His careful guidance, passion, and ceaseless experimentation turned copper and silver into canvases of luminous color—vivid stories coaxed from fire.

Bates’ influence didn’t stop with his own remarkable work. His students—and their students—carried these techniques and philosophies across the country. They breathed new life into ancient practices, pushing boundaries, forging modernist jewelry, and proving again that craft is a lineage of both skill and heart. From delicate cloisonné to bold abstract panels, the legacy of Ohio’s enameling pioneers lives on in countless studios today.

Now, more than a century later, we find ourselves in the midst of a quiet renaissance. Enameling is blooming all over again. Artists across Ohio and the broader American craft community are drawing luminous narratives from their kilns. You can spot these vibrant creations at art fairs, intimate gallery shows, and shared proudly across social media—sparking wonder in the most ordinary of moments.

As makers and appreciators, we inherit more than just technique. We inherit a way of seeing: of honoring process, of caring deeply for materials, of leaving thoughtful traces behind for others to build on. What we create, teach, and pass along becomes part of a ripple that can extend long after we are gone.

So here’s to Kenneth F. Bates, to Ohio’s enduring fire, and to all of us still tending it—one brushstroke of enamel, one hand-raised torch at a time. May we continue to experiment, to teach, to create, so that the next generation has something luminous and lasting to stand upon.

John Paul Miller: Ohio’s Master of Gold Dust and Dream Creatures

This morning, I found myself thinking about the quiet revolutions that happen in small studios — the alchemy of patience, fire, and human hands. It brought me back to John Paul Miller, a name that hums through the history of American metalsmithing like a well-kept secret.

Miller is often hailed as the father of American granulation. If you’re not familiar, granulation is a near-mystical process of fusing hundreds — sometimes thousands — of minute gold or silver spheres onto the surface of a piece, building delicate constellations of metal that catch the light like a galaxy trapped in amber.

It’s an ancient art. The oldest known example was found in the royal tomb of Queen Pu-Abi in Ur, Sumer — five thousand years ago. Imagine: Miller’s goldsmith’s bench in Cleveland somehow linked by an unbroken filament of craft to the palace workshops of Mesopotamia.

Though born in 1918 in Huntington, Pennsylvania, Miller’s heart and legacy are purely Ohio. As a child, his family settled in Cleveland, where he began taking Saturday art classes at the Cleveland School of Art (now the Cleveland Institute of Art). After high school, he returned there to formally study Design and Industrial Arts. Even then, he was sketching out a life that wove together beauty and utility.

World War II briefly pulled him away. Enlisted in the Army, his artistic gifts found their place designing maps and instructional manuals for the Training Literature Department of the Armed Forces. But after the war’s echo faded, Cleveland called him back, and the School welcomed him home — this time to teach. It was there, among the earnest chatter of students and the quiet hum of studio tools, that Miller truly sank into metalsmithing. Silver, gold, enamel — he chased their secrets with a devotion that bordered on spiritual.

Granulation, however, would become his lasting signature. Unlike many modern jewelers, Miller turned backward through time, studying Etruscan and Sumerian pieces, experimenting relentlessly to master their elusive techniques. By the time he succeeded, he wasn’t simply reviving an old art form; he was reinventing it, leaving behind brooches and rings that feel like something plucked from a myth — alive with tiny fantastical creatures and the shimmer of gold dust.

“There’s no question I wanted it to be beautiful,” Miller once said.

“I didn’t want it to be kinky or unique particularly or something that was avant-garde or anything. I just wanted it to be beautiful.”

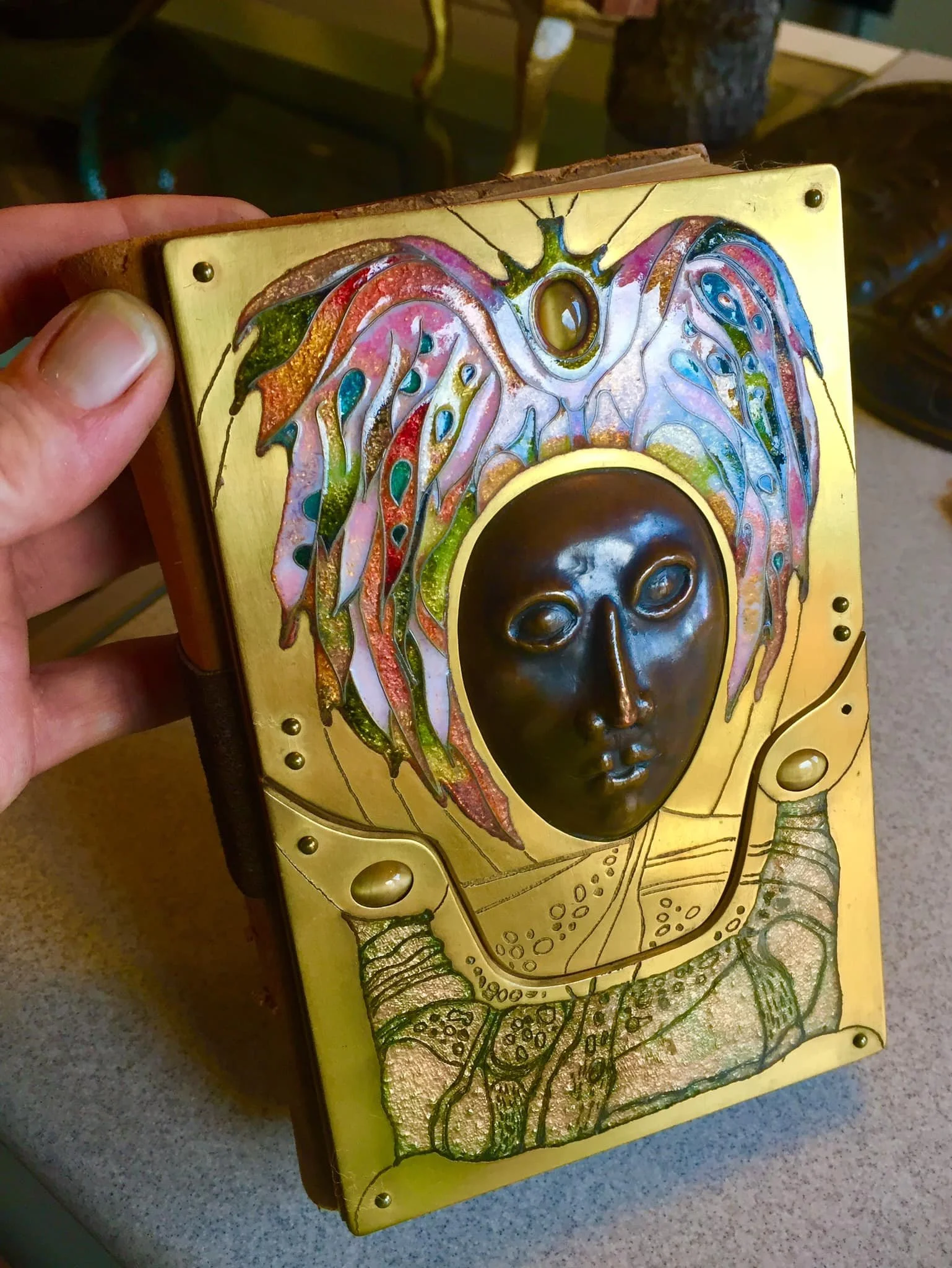

And beautiful it was. His jewelry is a menagerie of small wonders — seahorses, lizards, delicate insects — rendered in granulated gold and vibrant enamel. Pieces that, even decades later, still seem to breathe.

Miller remained in Cleveland all his life, passing in 2013, surrounded by people who loved him not only for his brilliance at the bench but for his gentle nature. Those who knew him speak of a lifelong artist, a humble teacher, and a man deeply in tune with the natural world he so often immortalized in metal.

In a field sometimes driven by ego and novelty, Miller stood apart, chasing neither shock nor spectacle. He pursued beauty — pure and simple — and in doing so, he left an indelible mark not just on American studio jewelry, but on the very language of ornament.

So here’s to John Paul Miller:

Cleveland craftsman, alchemist of ancient gold, tender conjurer of dream beasts — proof that sometimes, the most profound revolutions begin quietly, in the heart of Ohio.

Mary Ellen McDermott: Akron’s Enamel Luminary Who Dared to Change the Course of Metalsmithing

This morning, as the first hush of daylight slipped across my studio table and steam rose from my chipped mug, I found myself searching for an artist to write about—someone who had altered the course of metalsmithing history and, with any luck, had roots tangled close to my own in Ohio soil.

I thought of John Paul Miller and his golden granulations—Cleveland’s proud son—and nearly reached for my phone to text my dear friend, the ever-encyclopedic jewelry historian Jason Adams, for a spark of inspiration. But before my thumb could dance across the screen, a name, long stored in the attic of my mind, unfurled itself like a ribbon.

Mary Ellen McDermott.

An artist not just from Ohio, but from Akron—my own stomping grounds, city of tire kings and tireless makers. A woman who moved through a mid-century world with grace and ferocity, redefining what studio jewelry could be, one luminous enamel panel at a time.

I first crossed paths with Mary Ellen’s legacy in 2017, while co-curating a metalsmithing and enameling exhibition at the Peninsula Art Academy. Carol Adams, my co-curator and an Akron art legend in her own right, caught my arm, looked me squarely in the eyes, and said, with all the weight of history behind her:

“Do you know who this is?”

She was pointing to a collection of works by Mary Ellen McDermott—pieces so radiant with color and possibility they seemed to vibrate under the gallery lights. During that show, I was even lucky enough to hold some of Mary Ellen’s historical pieces in my own hands, borrowed from her foundation. (My hand, immortalized, ended up right on the cover of the show’s book.)

Akron is often overshadowed by Cleveland’s industrial arts heritage, but here was proof that our city, too, had birthed a titan. Born Mary Ellen Nichols in 1919, right in Akron’s embrace, she pursued an education at the Cleveland School of Art (now the Cleveland Institute of Art), graduating in 1940 with a BFA focused on painting, watercolor, fashion illustration, and jewelry design. Soon after, she married and took the name McDermott.

Her journey with enamel—a notoriously demanding medium—was not immediate. It wasn’t until around 1953, well into her thirties and after years teaching painting and drawing at the Akron Art Institute, that she truly began to explore its depths. Enamel is glass, ground into a powder so fine it whispers when poured, sifted onto copper sheets, then fired at 1700 degrees Fahrenheit until it melts into liquid light. These were not paintings. These were architectural works of art: vivid, large-scale sculptures made of earth’s oldest materials, fused by fire.

By 1961, at the age of 42, she returned to Cleveland to teach, ultimately rising to chair the Enamel on Metal Department by 1968. For nearly two decades she shaped a generation of artists there, known as a free spirit and a profoundly tolerant teacher who urged her students to chase the limits of what enamel could do. She was, in every sense, a force—a woman who carved a space for herself in a field dominated by men, and then threw open the door for countless others.

In a 1955 Cleveland Plain Dealer interview titled “Puts Her Art on Enamel Panels,” she captured her medium’s eternal allure:

“Enamel is one of the ageless art mediums. It is more permanent than oils and it never fades. You can get effects in enamel you can’t get in any other way because it is translucent and it looks precious to begin with.”

Imagine the audacity it took for a woman in mid-century Ohio—amid all the stiff collars and expectations—to stand before a roaring kiln and conjure such fragile, molten magic. To insist on a life of art. To become the teacher’s teacher.

Mary Ellen McDermott didn’t just change metalsmithing; she embodied its molten heart. She is a thread in Akron’s artistic tapestry that continues to glint brightly, reminding us what’s possible when talent meets fearless exploration.

Marie Zimmerman

Imagine being so undeniably good they simply couldn’t ignore you.

Marie Zimmermann (1879–1972) was that kind of extraordinary. Born in Brooklyn to Swiss parents, she mastered a dozen crafts—metalsmithing above all. Her hands conjured repoussé boxes alive with mythic beasts, silver bowls that rippled like water, gem-laced brooches that could’ve graced a pharaoh.

She wove ancient Greek, Egyptian, and Renaissance motifs into something utterly her own—a lush, American aesthetic that referenced centuries. Critics called her “perhaps the most versatile artist in the country.” Her works were scooped up by industrial titans, shown in major exhibitions, and today rest in the Met, the Art Institute of Chicago, and more.

Make no mistake: she had to be better.

In the early 1900s, for a woman to flourish in metalsmithing—let alone at this scale—she couldn’t simply match her male peers. She had to dazzle, astonish, transcend.

And transcend she did.

At a time when most women were confined to “delicate” arts, Marie rolled up her sleeves and did something nearly unheard of:

She directed a team of men—blacksmiths, silversmiths, casters—at the National Arts Club in New York.

Seasoned craftsmen took her lead, translating her fearless visions into wrought gates, chased silver, architectural fixtures, and intricate jewels. She didn’t just wield a hammer—she wielded authority, orchestrating workshops that blurred the line between object and poetry.

Zimmermann made her living through commissions—bronze doors for estates, ecclesiastical silver, jewelry for New York’s elite. Yet she lived largely on her own terms, never marrying, finding solace at her beloved farm in Pike County, PA.

Though celebrated in her day, her story still feels like a hidden treasure waiting to be unearthed by those who truly understand what it took to stand at the helm of a metals studio back then.

Marie Zimmermann was fire and alloy—beauty conjured from grit. She was not just a maker of objects, but a maker of possibilities, forging paths for all who’d come after.

If you didn’t know her name before, now you do.

Mary Lee Hu

There’s something about Marys (in Ohio).

Maybe it’s just coincidence, but I like to think it’s something in the rustbelt air — all that history of forging, bending, rebuilding — that keeps calling out to Marys to pick up metal and make it tender.

There’s Mary Ann Scherr, born in Akron, who turned jewelry into tools of care, designing beautiful trach necklaces and heart monitors that helped people feel seen, not just treated.

There’s Mary Ellen McDermott, who lived and taught in Akron, Peninsula, and Cleveland, painting copper with molten glass. Her enamel work shimmers like tiny stained glass windows you can hold in your hand.

And then there’s Mary Lee Hu, from Lakewood, who wove gold so fine it nearly breathed. She was born by Lake Erie in 1943 and somehow carried the lake’s rippling patience with her. Over decades, she twisted tiny loops of wire into fabric-like sculptures that drape across the body. It’s a choreography of hands, breath, and steady attention that feels so close to how many of us soothe ourselves — through slow, tactile making.

There’s no neat story of depression or illness to pin to Mary Lee Hu the way we might with an Agnes Martin or a Frida Kahlo. But you can feel the same meditative pull in her process: the tiny, deliberate gestures that take chaos and turn it into something intricate, gentle, and strong.

I love the grace of that. The idea that through repetition — whether carving cuttlebone or looping gold wire — we can quiet our own storms, if only for a little while.

If you’ve got a favorite artist whose hands worked like this — slowly, patiently, turning mess into meaning — I’d love to hear.