John Paul Miller: Ohio’s Master of Gold Dust and Dream Creatures

This morning, I found myself thinking about the quiet revolutions that happen in small studios — the alchemy of patience, fire, and human hands. It brought me back to John Paul Miller, a name that hums through the history of American metalsmithing like a well-kept secret.

Miller is often hailed as the father of American granulation. If you’re not familiar, granulation is a near-mystical process of fusing hundreds — sometimes thousands — of minute gold or silver spheres onto the surface of a piece, building delicate constellations of metal that catch the light like a galaxy trapped in amber.

It’s an ancient art. The oldest known example was found in the royal tomb of Queen Pu-Abi in Ur, Sumer — five thousand years ago. Imagine: Miller’s goldsmith’s bench in Cleveland somehow linked by an unbroken filament of craft to the palace workshops of Mesopotamia.

Though born in 1918 in Huntington, Pennsylvania, Miller’s heart and legacy are purely Ohio. As a child, his family settled in Cleveland, where he began taking Saturday art classes at the Cleveland School of Art (now the Cleveland Institute of Art). After high school, he returned there to formally study Design and Industrial Arts. Even then, he was sketching out a life that wove together beauty and utility.

World War II briefly pulled him away. Enlisted in the Army, his artistic gifts found their place designing maps and instructional manuals for the Training Literature Department of the Armed Forces. But after the war’s echo faded, Cleveland called him back, and the School welcomed him home — this time to teach. It was there, among the earnest chatter of students and the quiet hum of studio tools, that Miller truly sank into metalsmithing. Silver, gold, enamel — he chased their secrets with a devotion that bordered on spiritual.

Granulation, however, would become his lasting signature. Unlike many modern jewelers, Miller turned backward through time, studying Etruscan and Sumerian pieces, experimenting relentlessly to master their elusive techniques. By the time he succeeded, he wasn’t simply reviving an old art form; he was reinventing it, leaving behind brooches and rings that feel like something plucked from a myth — alive with tiny fantastical creatures and the shimmer of gold dust.

“There’s no question I wanted it to be beautiful,” Miller once said.

“I didn’t want it to be kinky or unique particularly or something that was avant-garde or anything. I just wanted it to be beautiful.”

And beautiful it was. His jewelry is a menagerie of small wonders — seahorses, lizards, delicate insects — rendered in granulated gold and vibrant enamel. Pieces that, even decades later, still seem to breathe.

Miller remained in Cleveland all his life, passing in 2013, surrounded by people who loved him not only for his brilliance at the bench but for his gentle nature. Those who knew him speak of a lifelong artist, a humble teacher, and a man deeply in tune with the natural world he so often immortalized in metal.

In a field sometimes driven by ego and novelty, Miller stood apart, chasing neither shock nor spectacle. He pursued beauty — pure and simple — and in doing so, he left an indelible mark not just on American studio jewelry, but on the very language of ornament.

So here’s to John Paul Miller:

Cleveland craftsman, alchemist of ancient gold, tender conjurer of dream beasts — proof that sometimes, the most profound revolutions begin quietly, in the heart of Ohio.

Mary Ellen McDermott: Akron’s Enamel Luminary Who Dared to Change the Course of Metalsmithing

This morning, as the first hush of daylight slipped across my studio table and steam rose from my chipped mug, I found myself searching for an artist to write about—someone who had altered the course of metalsmithing history and, with any luck, had roots tangled close to my own in Ohio soil.

I thought of John Paul Miller and his golden granulations—Cleveland’s proud son—and nearly reached for my phone to text my dear friend, the ever-encyclopedic jewelry historian Jason Adams, for a spark of inspiration. But before my thumb could dance across the screen, a name, long stored in the attic of my mind, unfurled itself like a ribbon.

Mary Ellen McDermott.

An artist not just from Ohio, but from Akron—my own stomping grounds, city of tire kings and tireless makers. A woman who moved through a mid-century world with grace and ferocity, redefining what studio jewelry could be, one luminous enamel panel at a time.

I first crossed paths with Mary Ellen’s legacy in 2017, while co-curating a metalsmithing and enameling exhibition at the Peninsula Art Academy. Carol Adams, my co-curator and an Akron art legend in her own right, caught my arm, looked me squarely in the eyes, and said, with all the weight of history behind her:

“Do you know who this is?”

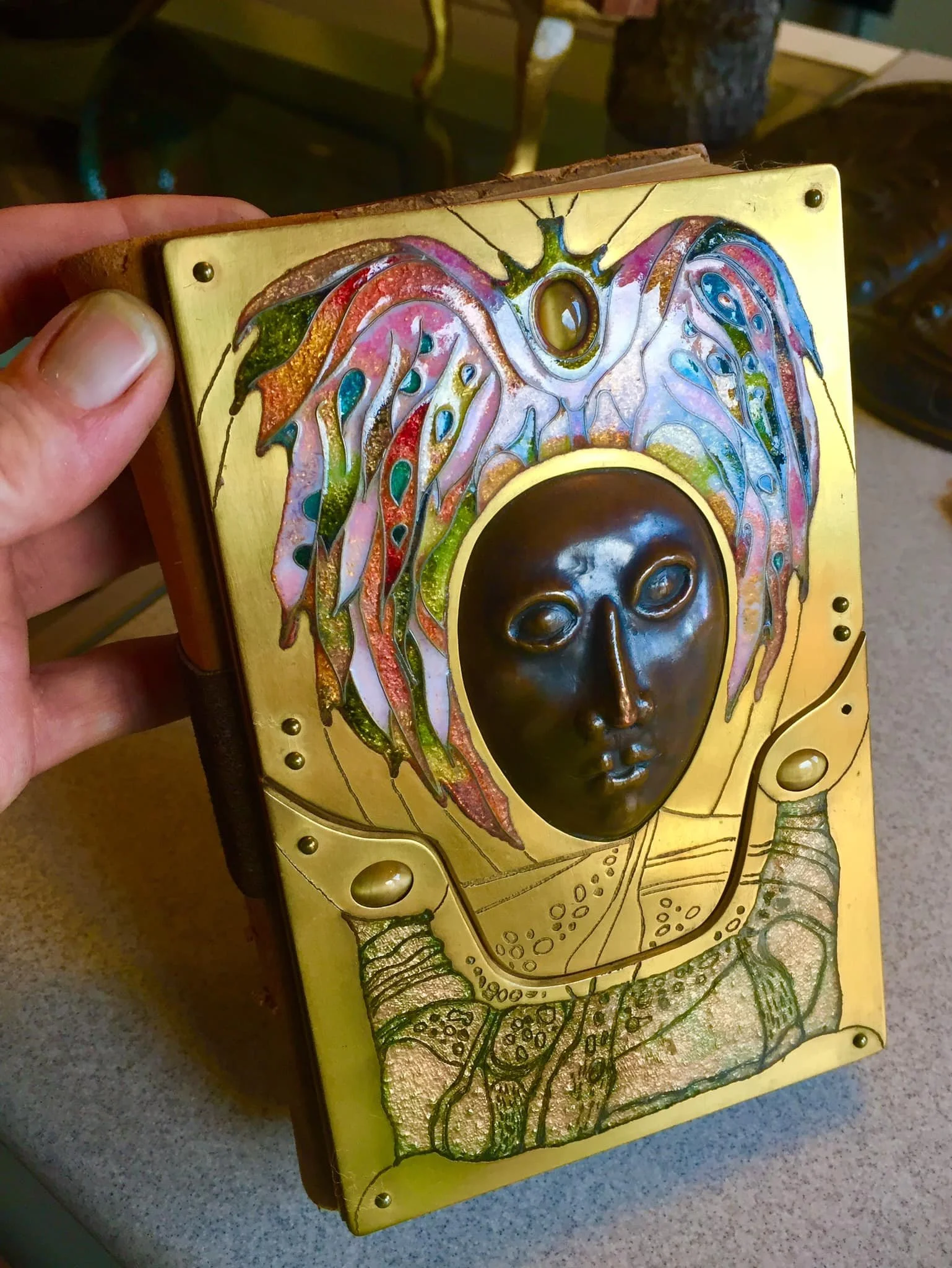

She was pointing to a collection of works by Mary Ellen McDermott—pieces so radiant with color and possibility they seemed to vibrate under the gallery lights. During that show, I was even lucky enough to hold some of Mary Ellen’s historical pieces in my own hands, borrowed from her foundation. (My hand, immortalized, ended up right on the cover of the show’s book.)

Akron is often overshadowed by Cleveland’s industrial arts heritage, but here was proof that our city, too, had birthed a titan. Born Mary Ellen Nichols in 1919, right in Akron’s embrace, she pursued an education at the Cleveland School of Art (now the Cleveland Institute of Art), graduating in 1940 with a BFA focused on painting, watercolor, fashion illustration, and jewelry design. Soon after, she married and took the name McDermott.

Her journey with enamel—a notoriously demanding medium—was not immediate. It wasn’t until around 1953, well into her thirties and after years teaching painting and drawing at the Akron Art Institute, that she truly began to explore its depths. Enamel is glass, ground into a powder so fine it whispers when poured, sifted onto copper sheets, then fired at 1700 degrees Fahrenheit until it melts into liquid light. These were not paintings. These were architectural works of art: vivid, large-scale sculptures made of earth’s oldest materials, fused by fire.

By 1961, at the age of 42, she returned to Cleveland to teach, ultimately rising to chair the Enamel on Metal Department by 1968. For nearly two decades she shaped a generation of artists there, known as a free spirit and a profoundly tolerant teacher who urged her students to chase the limits of what enamel could do. She was, in every sense, a force—a woman who carved a space for herself in a field dominated by men, and then threw open the door for countless others.

In a 1955 Cleveland Plain Dealer interview titled “Puts Her Art on Enamel Panels,” she captured her medium’s eternal allure:

“Enamel is one of the ageless art mediums. It is more permanent than oils and it never fades. You can get effects in enamel you can’t get in any other way because it is translucent and it looks precious to begin with.”

Imagine the audacity it took for a woman in mid-century Ohio—amid all the stiff collars and expectations—to stand before a roaring kiln and conjure such fragile, molten magic. To insist on a life of art. To become the teacher’s teacher.

Mary Ellen McDermott didn’t just change metalsmithing; she embodied its molten heart. She is a thread in Akron’s artistic tapestry that continues to glint brightly, reminding us what’s possible when talent meets fearless exploration.